Baccalauréat S Antilles Guyane 22 juin 2015 - Correction Exercice 1

Correction de l'exercice 1 (5 points)

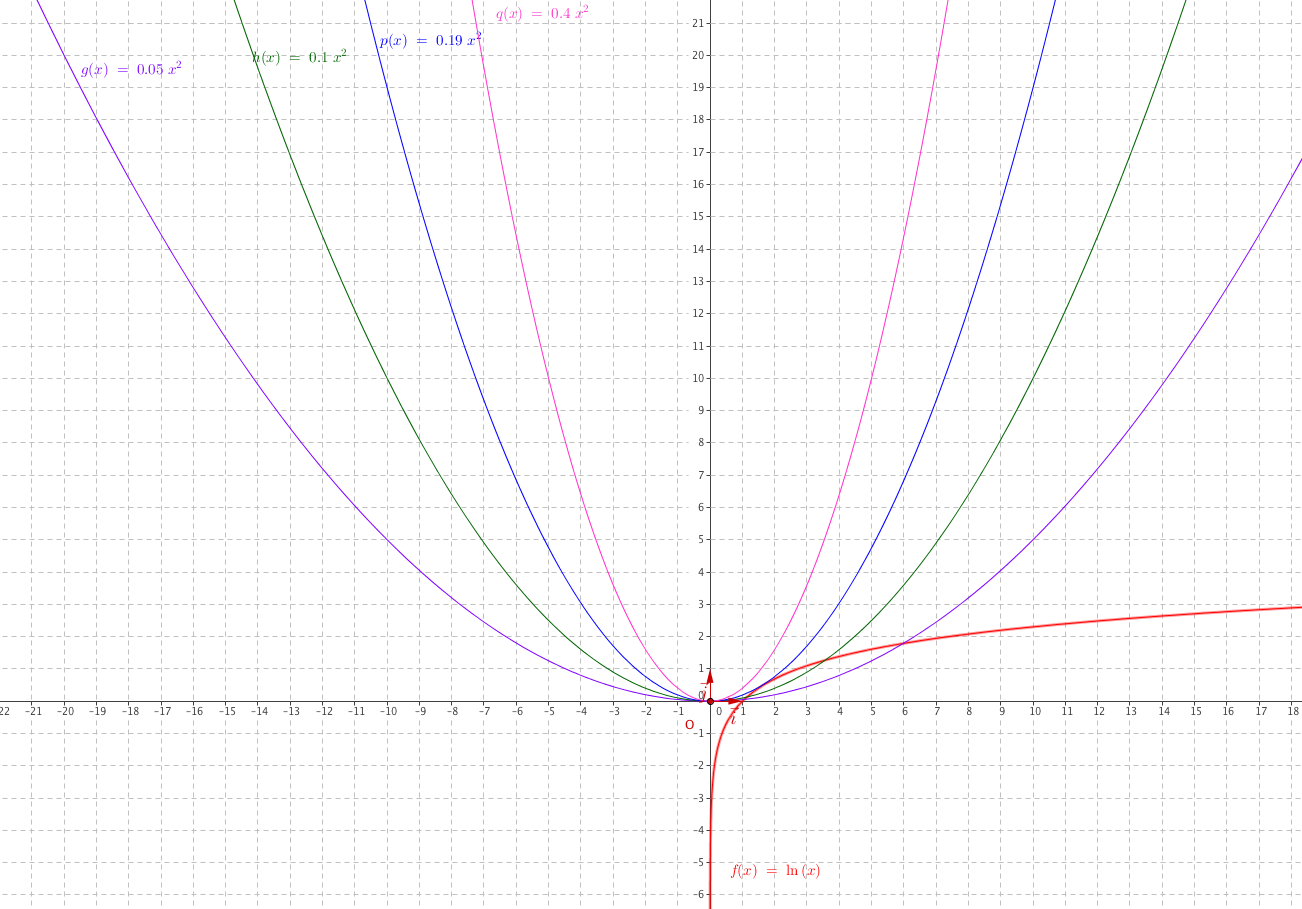

Soit $f$ la fonction définie sur l'intervalle $]0~;~+ \infty[$ par $f(x) = \ln x$. Pour tout réel $a$ strictement positif, on définit sur $]0~;~+ \infty[$ la fonction $g_a$ par $g_a(x) = ax^2$. On note $\mathcal{C}$ la courbe représentative de la fonction $f$ et $\Gamma_a$ celle de la fonction $g_a$ dans un repère du plan. Le but de l'exercice est d'étudier l'intersection des courbes $\mathcal{C}$ et $\Gamma_a$ suivant les valeurs du réel strictement positif $a$.

Partie A

On a construit( en annexe 1 à rendre avec la copie ) les courbes $\mathcal{C}$, $\Gamma_{0,05}$, $\Gamma_{0,1}$, $\Gamma_{0,19}$ et $\Gamma_{0,4}$.

- Nommer les différentes courbes sur le graphique. Aucune justification n'est demandée.

- Utiliser le graphique pour émettre une conjecture sur le nombre de points d'intersection de$\mathcal{C}$ et $\Gamma_a$ suivant les valeurs (à préciser) du réel $a$. Il semblerait que :

– si $0<a<0,19$, $\mathscr{C}$ et $\Gamma_a$ ont deux points d’intersection

– si $a=0,19$, $\mathscr{C}$ et $\Gamma_a$ ont un point d’intersection

– si $a > 0,19$, $\mathscr{C}$ et $\Gamma_a$ n’ont aucun point d’intersection

Partie B

Pour un réel $a$ strictement positif, on considère la fonction $h_a$ définie sur l'intervalle $]0~;~+ \infty[$ par \[h_a(x) = \ln x - ax^2.\]

- Justifier que $x$ est l'abscisse d'un point $M$ appartenant à l'intersection de $\mathcal{C}$ et $\Gamma_a$ si et seulement si $h_a (x) = 0.$ Soit $x$ l’abscisse d’un point M appartenant à l’intersection de $\mathscr{C}$ et $\Gamma_a$

-

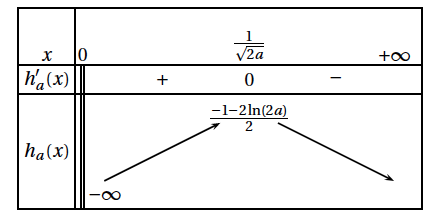

- On admet que la fonction $h_a$ est dérivable sur $]0~;~+ \infty[$, et on note $h'_a$ la dérivée de la fonction $h_a$ sur cet intervalle. Le tableau de variation de la fonction ha est donné ci-dessous. Justifier, par le calcul, le signe de $h'_a(x)$ pour $x$ appartenant à $]0~;~+ \infty[$.

D’après l »énoncé, $h_a$ est dérivable sur $]0;+\infty[$.

D’après l »énoncé, $h_a$ est dérivable sur $]0;+\infty[$. - Rappeler la limite de $\frac{\ln x}{x}$ en $+ \infty$. En déduire la limite de la fonction $h_a$ en $+ \infty$. On ne demande pas de justifier la limite de $h_a$ en $0$. $\lim\limits_{x \to +\infty} \dfrac{\ln x}{x} =0$

$h'(x) = \dfrac{1}{x} – 2ax = \dfrac{1 – 2ax^2}{x}$

$\quad$

$$\begin{array}{rl} h'(x) \ge 0 &\iff 1 – 2ax^2 \ge 0 \\ & \iff \left(1 – \sqrt{2a}x\right)\left(1 + \sqrt{2a}x\right) \ge 0 \\ & \iff \left(1 – \sqrt{2a}x\right) \ge 0 \quad \text{ car } \left(1 + \sqrt{2a}x\right) > 0 \\\ & \iff 1 \ge \sqrt{2a}x \\ & \iff x \le \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2a}}\end{array}$$

Ainsi $h'(a) > 0$ sur $\left]0;\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2a}} \right[$

$h'\left(\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2a}}\right) = 0 $

$h'(a)<0$ sur $\left]\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2a}};+\infty\right[$

$\quad$

$\quad$

$h_a(x) =x\left(\dfrac{\ln x}{x} – ax\right)$

$\lim\limits_{x \to +\infty} -ax = -\infty$ car $a> 0$

Donc $\lim\limits_{x \to +\infty}\left(\dfrac{\ln x}{x} – ax\right) = -\infty$

Finalement $\left(\dfrac{\ln x}{x} – ax\right) h_a(x) = -\infty$ - On admet que la fonction $h_a$ est dérivable sur $]0~;~+ \infty[$, et on note $h'_a$ la dérivée de la fonction $h_a$ sur cet intervalle. Le tableau de variation de la fonction ha est donné ci-dessous. Justifier, par le calcul, le signe de $h'_a(x)$ pour $x$ appartenant à $]0~;~+ \infty[$.

- Dans cette question et uniquement dans cette question, on suppose que $a = 0,1$.

- Justifier que, dans l'intervalle $\left]0~;~\frac{1}{\sqrt{0,2}}\right]$, l'équation $h_{0,1}(x) = 0$ admet une unique solution. On admet que cette équation a aussi une seule solution dans l'intervalle $]0~;~+ \infty[$.

- \(\1 \) est une fonction dérivable (donc continue) sur l' intervalle \(I = \left]\2 ; \3\right]\).

- \(\1\) est strictement croissante sur l' intervalle \(I = \left]\2 ; \3\right]\).

- \(\lim\limits_{x \to \2}~\1(x)=\4\) et \(\1 \left(\3\right)=\5\)

- Quel est le nombre de points d'intersection de $\mathcal{C}$ et $\Gamma_{0,1}$ ?

D'après le théorème de la bijection :

\(\1\) réalise donc une bijection de \(\left]\2 ; \3\right]\) sur \(\left]\4;\5\right]\)

\(\6\in \left]\4;\5\right]\),

donc l'équation \(\1(x) = \6 \) a une racine unique \(\7\) dans \(\left]\2 ; \3\right]\) .

|-\infty|\frac\{\ln 5 -1\}{2\}|0|\alpha} L’équation $h_{0,1} = 0$ possède une solution sur chacun des intervalles $\left]0;\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{0,2}}\right]$ et $\left]\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{0,2}};+\infty\right[$. - Dans cette question et uniquement dans cette question, on suppose que $a = \frac{1}{2\text{e}}$.

- Déterminer la valeur du maximum de $h_{\frac{1}{2\text{e}}}$. $h_{\frac{1}{2\text{e}}}\left(\sqrt{ \text{e}}\right)= \dfrac{-1 – \ln \text{e}^{-1}}{2} = \dfrac{-1 +1}{2} = 0$.

- En déduire le nombre de points d'intersection des courbes $\mathcal{C}$ et $\Gamma_{\frac{1}{2\text{e}}}$. Justifier. La fonction $h_{\frac{1}{2\text{e}}}$ admet donc $0$ comme maximum, atteint seulement en $\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{\dfrac{1}{2\text{e}}}} = \sqrt{\text{e}}$.

Ainsi $\mathscr{C}$ et $\Gamma_{\frac{1}{2\text{e}}}$ n’ont qu’un seul point d’intersection. - Quelles sont les valeurs de $a$ pour lesquelles $\mathcal{C}$ et $\Gamma_{a}$ n'ont aucun point d'intersection ? Justifier. $\mathscr{C}$ et $\Gamma_a$ n’ont aucun point d’intersection

On a donc $f(x) = g_a(x) \iff f(x) – g_a(x)=0 \iff \ln x – ax^2 = 0$.

Ainsi $\mathscr{C}$ et $\Gamma_{0,1}$ ont deux points d’intersection.

$$\begin{array}{rl} &\iff \dfrac{-1 – \ln(2a)}{2} <0 \\ &\iff -1 – \ln(2a) < 0 \\ &\iff -\ln(2a) < 1 \\ & \iff \ln(2a) > -1 \\ & \iff 2a > \text{e}^{-1} \\ & \iff a > \dfrac{1}{2\text{e}}\end{array}$$

- Vues: 27923